-

Call your local health authority

Health Link BC: Dial 811

Never touch a bat, dead or alive, with your bare hands

The risk of getting rabies is extremely low but if contracted the disease is fatal if left untreated.

The human vaccine is excellent, involving shots in the arm, and not in the stomach like older versions of the vaccine.

-

Call Your Vet

It is important to always keep your pets up to date on their rabies vaccines, especially outdoor cats who are known to hunt bats.

RABIES- How big is the risk?

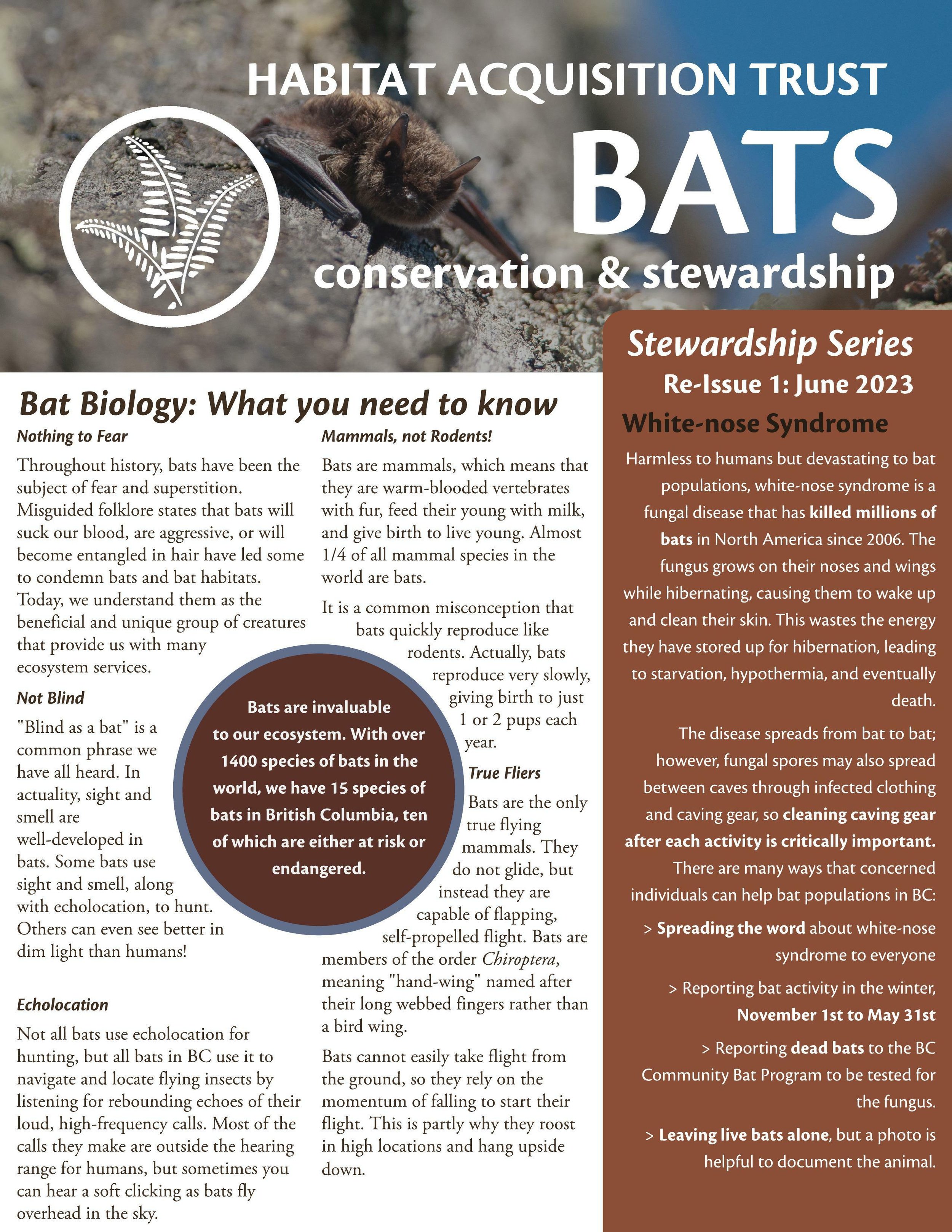

Bats have developed a poor reputation as being the main transmitters of rabies, and this is one of the reasons that people fear them. Bats are a reservoir for rabies in BC – meaning they can carry the disease and pass it on without showing signs of the disease themselves. However, the percentage of bats that have rabies has been over-estimated in North America, because samples were taken primarily from sick or dead bats. When normal populations of bats are sampled randomly, less than 0.5% of bats tested positive for rabies.

Rabies is a serious illness that can be fatal; nevertheless, contracting rabies from a bat is extremely rare. Since 1970, five people have died from rabies in Canada and four of these deaths followed exposure to bats. Bats should not be feared, but caution should be taken.

Bats with rabies may appear sick and weak, and be more likely to be somewhere where people can come in contact – e.g. on the ground. People should beware of bats that act strangely, such as bats flying during the day, and NEVER pick up a sick or dead animal with bare hands; use gloves or a shovel to gently move the animal away from human activity if possible, or call your local Community Bat Project for advice.

If You Find a Bat

If you find a bat alive or dead on the ground it should be left alone if possible. If there’s a risk that the bat will come into contact with a person or a pet, it should be moved using thick gloves and a shoe box.

If a bat flies into your building, often these bats are juveniles learning to fly. The bat will usually find its own way out. Open all the windows and doors leading to the outside and watch the bat to make sure it leaves. If it does not, wait until it has landed on something, and use thick gloves and a shoe box to move it to safety.

To move a bat: Wear gloves (such as oven mitts or thick gardening gloves), and place a small can or box over the bat, while gently sliding thin cardboard under the container to “trap” the bat. Take the container, cardboard, and enclosed bat outside to release it. A bat should be placed on a wall or tree, high enough to avoid contact with children or pets. For sleeping or injured bats, put them in a pillow case and pin the pillow case high on a wall or tree with the open end up. Bats will crawl up and fly out when they are ready.

HAT’s Community Bat Program

HAT's Community Bat Program is trying to learn more about bats in our region to guide conservation efforts, to provide information to the public to help protect bat roost sites, enhance habitat through the placement of bat houses and bat-friendly gardening, and help homeowners who choose to evict bat colonies to do so in a way that harms the bats as little as possible.

-

The BC Annual Bat Count is a citizen science program to annually monitor bat populations in roost sites. Abandoned houses, barns, church steeples – and even currently-occupied structures – can provide a summer home to female bats and their young. Monitoring these “maternity colonies” can give biologists a good idea of how bat populations in an area are doing from year to year. With the occurrence of White-nose Syndrome in North America, monitoring these colonies is more important than ever.

HAT annually coordinates the monitoring of 18 roosts in the Capital Regional District. If you would like to participate please visit this page.

-

HAT works with volunteers and contractors to build “BC bat appropriate” bat houses that we make available to land owners and managers whose properties would benefit from one.

We also work to ensure that information about how to identify and construct a proper bat house is made available to our local community.

If you would like to volunteer for our Bat Box building program please contact us at bat@hat.bc.ca

-

Many people are deeply uncomfortable with bats in their home or outbuildings. One of our goals is to help people who feel it is necessary to remove bats from their buildings do so in a way that harms the bats as little as possible.

HAT will visit homeowners with bat colonies and help them develop a plan to exclude the bats and provide some alternate place for them to roost and raise their young.

We will help you identify what time of year to exclude the bats, what renovations will reduce the chances of bats re-occupying your home, and find a place for a bat house for the colony to use.

Contact bat@hat.bc.ca if you have a colony and would like help with exclusions.

-

To learn more about bats, HAT uses a bat detector to do acoustic monitoring of bats and their colonies. With bats' rich array of echolocation behaviour and a bat detector, we can learn what species are in a colony (often more than 1 species occupies the same site), and learn what times of day and seasons bats are most active. Understanding bat behaviour, for instance, when pups first start to fly, is an important part of an effective conservation program. Acoustic monitoring is completely non-invasive - the detector simply listens to the bat echolocation calls.

-

In partnership with the Ministry of Environment, HAT is collecting guano for DNA analysis. This will provide the most accurate information about which species are in an area and how those species relate to one another. Guano is collected from the ground below the colony and there is no need to interfere with the bats.

-

HAT is mapping bat colonies so that non-invasive monitoring can be carried out (such as guano collection and acoustic monitoring).

Frequently Asked Bat Questions

-

Identification of any bat species isn’t easy. The Little Brown Myotis and the Yuma Myotis, for example, look the same, even in the hand. They are only identifiable by a DNA sample, usually collected in the form of guano. Other less certain methods include acoustic detection of their ultrasonic calls that can narrow down the species likely to be flying overhead. However, echolocation calls are not unique to each species so genetic sampling is needed to be certain. HAT works with the BC Community Bat Program to submit samples of guano for genetic testing from roosts across Southern Vancouver Island. If you have a roost and would like to identify the species, check out this document first

-

The pups can fly when they are a month old, but are still pretty clumsy and are reluctant to leave the roost for long. That is when people find bats in their homes – often a young bat is lost and looking for a safe place to roost.

Most small mammals have large litters and don’t live long, but bats are different. Typically having only 1 pup per year with a 50% survival rate means bat families are slow to grow. If they make it to adulthood, they can (Little Brown bats) live to be 30 years old.

-

Humans have shared buildings with bats for thousands of years, probably as early as first humans built living structures. These attic-dwelling bat species are defined as synanthropic, which means they have a strong ecological association with humans. Bats have been observed using buildings as roosting and foraging sites, temporary shelters, for reproduction and hibernation. Buildings have become an important resource for bats where natural roosting habitat is limited. For example, natural structures like wildlife trees (large trees with cavities or loose bark) are often felled because of forest harvesting or safety concerns.

This human association is for the bats’ own benefit and have adapted to these human structures over thousands of years. By taking up residence in these warmer human-made roosts, the bats have more energy stores for pregnancy and faster/safer development of their pups. They are also (in theory) less exposed to natural predators in urban environments. Although buildings can provide optimal conditions for roosting, bats in these structures are vulnerable to human disturbance or injury, either by intentional or accidental means. For more information about bats and buildings, visit this page.

-

There is no need to panic if you find bats in a building. Bats are simply small animals that are trying to find a suitable home. Some bat colonies can remain safely in buildings without creating a risk for humans. If you can become comfortable with bats in your building, we encourage you to learn to live with them. Bats do not damage buildings (remember they are not rodents), and an important colony may be relying on the site. The Community Bat Programs of BC provides some advice on how to live with bats.

The first step is to assess your situation. Are the bats causing a problem? If so, is it the bats themselves, or the side effects of the bats (such as noise, smell or guano) that are the issue? Leaving bats where they are is usually the best option for bat conservation but may not be an appropriate option for the homeowner. Check out the Living with Bats Guidebook that outlines how to successfully maintain a bat colony and be safe in your home. In order to do a full assessment of your home or building with bats, follow the steps in the Got bats: a BC Guide for Managing Bats in Buildings Guidebook

-

Unfortunately, a single bat house offers little variety in temperature, certainly much less than in a building. What they need is a variety of temperatures in their roosts called micro-climates. The preferred roost temperature varies with the seasons, with the gender of the roosting bats and with the age of the bats, particularly the pups.

Why is temperature important?

Even when bat boxes are used by those box-tolerant species, there is a problem. Bats get lots of protein by eating insects, but very little carbohydrates or fats, so bats have a very tight energy budget. To save energy, bats use a hibernation-like state called torpor to lower their metabolic rate and let the temperature in the roost help them maintain a required body temperature. Therefore, they can’t generate much heat on their own; they have to find roosts that offer the temperatures they need. For this reason it is best to have your bat box in the full sun, especially in the morning when the bats return home and the air is much colder.

-

No! Depending on the species of bat they might prefer rock crevices or dead trees and many of our local bats prefer to sleep alone. This diversity makes it pretty difficult to do much to conserve bats. Bat boxes aren't a suitable place for most species; they are used by 5 of the 9 species of bats we have here on Vancouver Island - Long-eared Myotis, Little Brown Myotis, Big Brown Bat, California Myotis and Yuma Myotis. Townsend's Big-eared Bats will roost in human structures like attics and barns, but they will not use typical bat boxes, unless they are very large. They require more open roost structures like mines or "bat condos" to roost happily. That means that bat conservation has to depend on us protecting the range of forest and wetland bat habitats. Learn more about BC bats here.

To report bats in your bat box or on your property fill out this form.

-

Unfortunately, bats are creatures of habit and if they have a current home that works perfectly for them they are unlikely to move. A bat box is a great way to make habitat available so that if a bat roost is destroyed nearby, they have somewhere to go.

In the meantime, make sure that your box(es) are as appealing as possible to the bats. One way to do this is to install more than one box to offer a variety of temperatures for them. Placement is critical, so bat boxes should be installed with advice from a local chapter of the BC Community Bat Program. To learn more about bat boxes, click here.

-

They do not transmit SARS-Cov-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Transmission is from people to people. That virus has not been found in any bat species in North America. Bats have “super immunity” - can carry lots of viruses without getting sick themselves (so might be a source of information to help us find a vaccine). Bats are not immune to rabies, but less than 1% carry the virus in BC. They sometimes catch it, but sicken and die. Therefore, don’t touch a sick-looking bat like one on the ground; but there’s little risk from live, healthy bats. However, it is a very serious disease, so never touch bats. If you would like to learn more about Bats and Human Health visit the BC Bats website.

To learn more about COVID-19 and bats, read this information bulletin.

-

· Report bats to the BC Community Bat Program

· Register your bat house or box with the Program and check for bat activity in the summer months

· Support organizations that are working locally to protect forest and wetland habitats like us!

· Advocate preserving our remaining old-growth forests (bats depend on them)

· Encourage friends/neighbours to keep the bats in their attics rather than forcing them out

· Volunteer for bats by participating in the Annual BC Bat Count

· Support a bat conservation group or program like the Adopt-a-Bat Campaign

About Bats

Bat’s are nocturnal mammals that play an extremely important role in the ecosystems of British Columbia.

There are 16 species of bat’s in BC and are protected by the BC Wildlife Act. The following 9 species are found on Vancouver Island:

BC List Blue Status is defined as: “Includes any native species or ecological community considered to be of Special Concern (formerly Vulnerable) in British Columbia. Species or ecological communities of Special Concern have characteristics that make them particularly sensitive or vulnerable to human activities or natural events. Blue-listed species or ecological communities are at risk, but are not Extirpated, Endangered or Threatened” (BC Systems & Ecosystems Explorer)

These 9 species of bats all have a few things in common:

All of our bats are insectivores, meaning they all eat bugs. In fact, they eat more insects than any other nighttime predator. What makes bats so handy to have around is that they eat many insects we consider to be pests, including mosquitoes. An adult lactating female can eat up to 3500 mosquitoes a night! No bats in Canada eat fruit or blood.

All of the bats in the region are relatively small. Most bats with their wings spread are smaller than adult's outspread hand, though a few grow up to 20cm.

All bats in BC are long-lived (over 30 years for some species) and reproduce slowly. Most species have only 1 baby each year, though a few species are known to have twins.

What’s the Problem?

All bats in British Columbia are suffering from major habitat loss, including loss of important feeding areas on streams and wetlands, and roost areas in wildlife trees. Insect populations are in decline because of insecticide use.